Unpleasant films

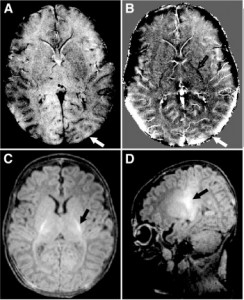

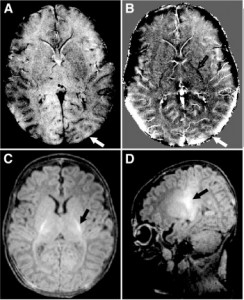

There’ve been times in my life when I imagined myself sort of a medical geek, but I doubt anybody wants to see images like this when a family member is involved. I didn’t. When our little boy was one week old, the doctor showed some films to his mom and me, and provided a summary of what they could mean, thereby transforming our joy of parenthood into an agony of fear, horror, and suspense. His scans were unusual but not necessarily significant, according to the doctor, and so we resolved to hope for the best. When things subsequently began to turn out badly, however, those films provided a convenient excuse for doctors to shrug and move on to the next patient. All this technology can be a wonderful thing, but it was not helpful in our case. That’s particularly true in retrospect. Joseph’s brain has been scanned several times over the years, and every doctor who has seen the films has had a different opinion. At this point, however, the verdict seems to be that they show nothing out of the ordinary at all.

There’ve been times in my life when I imagined myself sort of a medical geek, but I doubt anybody wants to see images like this when a family member is involved. I didn’t. When our little boy was one week old, the doctor showed some films to his mom and me, and provided a summary of what they could mean, thereby transforming our joy of parenthood into an agony of fear, horror, and suspense. His scans were unusual but not necessarily significant, according to the doctor, and so we resolved to hope for the best. When things subsequently began to turn out badly, however, those films provided a convenient excuse for doctors to shrug and move on to the next patient. All this technology can be a wonderful thing, but it was not helpful in our case. That’s particularly true in retrospect. Joseph’s brain has been scanned several times over the years, and every doctor who has seen the films has had a different opinion. At this point, however, the verdict seems to be that they show nothing out of the ordinary at all.

Books to guide and encourage grownups

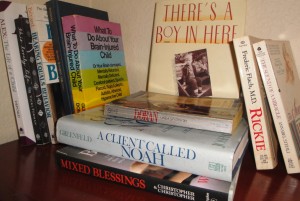

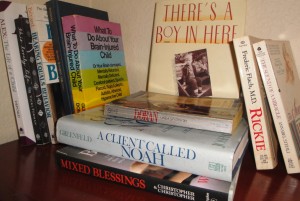

Imagine you’re a clueless new parent coming to terms with the realization that your child may have developmental problems. Imagine further the loneliness you may feel after consulting professionals who aren’t prepared to do much to remedy those problems: The child’s future is entirely in your hands. His needs may be urgent, but they’re a mystery, even to the experts. What do you know? This was the point at which Judy and I began trying to educate ourselves in hopes of improving things on our own. There are scenes in the print and (hopefully upcoming) film versions of What About the Boy? that show how our thwarted energy found direction when we discovered a new book—and there were far more such books than I wrote about. First there was a maverick provider’s manifesto with the promise that better answers were available. Then there were parents like us telling how those answers worked for them. Later, there were other providers with other ideas, and other parents–and even one or two recovered patients—weighing in on how it all shook out for them. We cherished these stories because they filled a void, albeit imperfectly. Years later, WATB became my contribution to the literature.

Imagine you’re a clueless new parent coming to terms with the realization that your child may have developmental problems. Imagine further the loneliness you may feel after consulting professionals who aren’t prepared to do much to remedy those problems: The child’s future is entirely in your hands. His needs may be urgent, but they’re a mystery, even to the experts. What do you know? This was the point at which Judy and I began trying to educate ourselves in hopes of improving things on our own. There are scenes in the print and (hopefully upcoming) film versions of What About the Boy? that show how our thwarted energy found direction when we discovered a new book—and there were far more such books than I wrote about. First there was a maverick provider’s manifesto with the promise that better answers were available. Then there were parents like us telling how those answers worked for them. Later, there were other providers with other ideas, and other parents–and even one or two recovered patients—weighing in on how it all shook out for them. We cherished these stories because they filled a void, albeit imperfectly. Years later, WATB became my contribution to the literature.

Daily scorecard

When we started a neurological stimulation program for Joseph, based on directions given by an organization back East (the Institutes), we had an assignment to perform various tasks with him throughout the day. That assignment changed, and generally became more complicated and demanding, each time we returned for a reevaluation. I made checkoff sheets for each day, to help us stay on track, and this is an example. It looks like some of the items on this day’s list weren’t accomplished, which is not surprising. It was a rare day indeed on which we met every goal. At this particular point in Joseph’s trajectory, the top priority was to get him walking. This was probably a “marathon” day for walks back and forth under his overhead ladder (OHL), and apparently he slightly surpassed that target (at the expense of meeting others).

When we started a neurological stimulation program for Joseph, based on directions given by an organization back East (the Institutes), we had an assignment to perform various tasks with him throughout the day. That assignment changed, and generally became more complicated and demanding, each time we returned for a reevaluation. I made checkoff sheets for each day, to help us stay on track, and this is an example. It looks like some of the items on this day’s list weren’t accomplished, which is not surprising. It was a rare day indeed on which we met every goal. At this particular point in Joseph’s trajectory, the top priority was to get him walking. This was probably a “marathon” day for walks back and forth under his overhead ladder (OHL), and apparently he slightly surpassed that target (at the expense of meeting others).

Reflex mask (aka “kiddie space mask”)

Little kids and plastic bags do not mix. That’s a given. But this is one example of various specially designed masks that were provided by the Institutes to parents of developmentally disabled kids. According to the Institutes (and some organizations they dismissed as imitators), the crux of each kid’s problem was inadequate breathing. Fix the breathing and within a matter of months the kid too might be fixed. Accordingly, while on program with the Institutes, we lived with a continuously-running seven-minute timer. When it beeped, we popped a mask such as this over our son’s mouth and nose for a one-minute duration. During that minute, the air he breathed had to be drawn in through that little straw in the end. He responded by breathing more deeply. (I still remember the surprise I felt at seeing an immobile kid puffing as if he’d just finished a sprint. Of course, getting to the point of actually being able to sprint would be better, and was one of the long-range program objectives.) Also, because he also inhaled a greater concentration of carbon dioxide while wearing the mask, changes occurred in his body that increased the blood flow to his brain. We saw reasons to believe that masking helped Joseph on a physiological level. Naturally, this paragraph does not constitute medical advice and is not intended as such.

Little kids and plastic bags do not mix. That’s a given. But this is one example of various specially designed masks that were provided by the Institutes to parents of developmentally disabled kids. According to the Institutes (and some organizations they dismissed as imitators), the crux of each kid’s problem was inadequate breathing. Fix the breathing and within a matter of months the kid too might be fixed. Accordingly, while on program with the Institutes, we lived with a continuously-running seven-minute timer. When it beeped, we popped a mask such as this over our son’s mouth and nose for a one-minute duration. During that minute, the air he breathed had to be drawn in through that little straw in the end. He responded by breathing more deeply. (I still remember the surprise I felt at seeing an immobile kid puffing as if he’d just finished a sprint. Of course, getting to the point of actually being able to sprint would be better, and was one of the long-range program objectives.) Also, because he also inhaled a greater concentration of carbon dioxide while wearing the mask, changes occurred in his body that increased the blood flow to his brain. We saw reasons to believe that masking helped Joseph on a physiological level. Naturally, this paragraph does not constitute medical advice and is not intended as such.

Homemade intelligence materials

“I just wish it were as easy to make a paralyzed kid walk as it is to make a brain-injured kid bright.” So said Glenn Doman when encouraging families on the program to go home and work hard to teach their kids about the world. Many reasons were given for doing this. Learning to read, learning to do mental math, learning about related subjects (breeds of dogs, flags of countries, famous people, or in this example WWII airplanes)–these activities would be fun, for parent and kid alike. Success would be easily achieved, and would therefore motivate efforts in other endeavors. And, yes, along the way the kid would become a lot smarter. We made all these materials in our spare time (ha ha; that means times when normal people were sleeping), and I hope it’s evident from this that we shot for maximum quality. There were moments when Joseph rewarded our efforts. But usually he was not much given to providing feedback.

“I just wish it were as easy to make a paralyzed kid walk as it is to make a brain-injured kid bright.” So said Glenn Doman when encouraging families on the program to go home and work hard to teach their kids about the world. Many reasons were given for doing this. Learning to read, learning to do mental math, learning about related subjects (breeds of dogs, flags of countries, famous people, or in this example WWII airplanes)–these activities would be fun, for parent and kid alike. Success would be easily achieved, and would therefore motivate efforts in other endeavors. And, yes, along the way the kid would become a lot smarter. We made all these materials in our spare time (ha ha; that means times when normal people were sleeping), and I hope it’s evident from this that we shot for maximum quality. There were moments when Joseph rewarded our efforts. But usually he was not much given to providing feedback.

The corner bar (not what it sounds like)

WATB includes a photo of Joseph walking beneath his overhead ladder. What we see here was a precursor to that. (I called it “Joe’s Bar.”) The first objective was to get him to grip an overhead dowel in order to stand up straight, and you can see the poor guy looks a little fearful at this point. Later, he learned to reach from one dowel to another, walking as he did so. And finally, at long last, he walked out from under the contraption with no assistance. We had him walking back and forth under the ladder for more than a year, but finally (at 39 months of age) Joseph became an independent walker. It was his clearest and most dramatic victory, and he was quite obviously proud of himself.

WATB includes a photo of Joseph walking beneath his overhead ladder. What we see here was a precursor to that. (I called it “Joe’s Bar.”) The first objective was to get him to grip an overhead dowel in order to stand up straight, and you can see the poor guy looks a little fearful at this point. Later, he learned to reach from one dowel to another, walking as he did so. And finally, at long last, he walked out from under the contraption with no assistance. We had him walking back and forth under the ladder for more than a year, but finally (at 39 months of age) Joseph became an independent walker. It was his clearest and most dramatic victory, and he was quite obviously proud of himself.

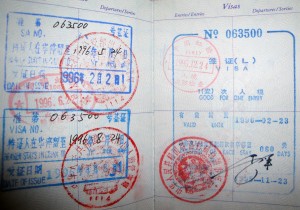

Travel docs

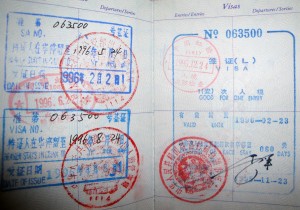

In Joseph’s early years our family did not take vacations. However, we traveled quite a lot. We flew from our home in San Diego to the Institutes in Philadelphia nine times over a period of four years. We made innumerable day-trips to clinics in places like LA and Phoenix. And after moving on from the Institutes’ program, we ventured abroad, always hoping to find someone who knew more than the last resource. It’s easy to look back at all that chasing about and see desperation, but everything we did made perfect sense (to us) at the time. In the process, I very slowly learned the importance of weighing the objective likelihood of success against the cost. Consequently, it’s been easier to pass up more recent opportunities to do the same thing. On the other hand, I’m still glad to have had the opportunity to try everything, and find out for myself that it didn’t work. (Say, Edison said something along those lines.)

In Joseph’s early years our family did not take vacations. However, we traveled quite a lot. We flew from our home in San Diego to the Institutes in Philadelphia nine times over a period of four years. We made innumerable day-trips to clinics in places like LA and Phoenix. And after moving on from the Institutes’ program, we ventured abroad, always hoping to find someone who knew more than the last resource. It’s easy to look back at all that chasing about and see desperation, but everything we did made perfect sense (to us) at the time. In the process, I very slowly learned the importance of weighing the objective likelihood of success against the cost. Consequently, it’s been easier to pass up more recent opportunities to do the same thing. On the other hand, I’m still glad to have had the opportunity to try everything, and find out for myself that it didn’t work. (Say, Edison said something along those lines.)

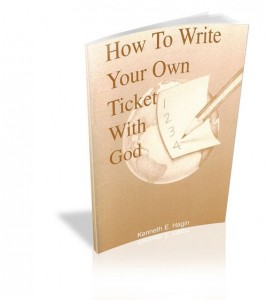

Articles of faith

The campaign to help our son was always an uphill struggle, but we experienced exciting victories along the way, and spotted little clues suggesting that still greater breakthroughs could be within reach. So we always believed success was possible. We also believed beyond any shadow of a doubt that success, i.e., total wellness, was his birthright. The challenge was simply finding the best path for attaining it. When our own efforts proved insufficient, we gradually began to think we needed a more spiritual approach. We were very ignorant of such matters, but highly motivated to learn. Accordingly, we started out in a quasi-New Age church that was very much into something called affirmations, i.e., calling things that be not as though they are, with the intent of summoning them into being. Growing dissatisfied with that, we found a movement that seemed more Bible-based and therefore hopefully closer to the source. (For example, the four steps suggested in the image to the left are derived from Mark 5:25-34.) Because of this endeavor, Joseph spent a fair amount of time when he was five and six years old in huge religious conventions and healing services. And his mom and I subsequently spent time coming to terms with the fact that we were either abject failures at this or else were still getting bad instruction. Still, hope is a wonderful thing, and we found some here.

The campaign to help our son was always an uphill struggle, but we experienced exciting victories along the way, and spotted little clues suggesting that still greater breakthroughs could be within reach. So we always believed success was possible. We also believed beyond any shadow of a doubt that success, i.e., total wellness, was his birthright. The challenge was simply finding the best path for attaining it. When our own efforts proved insufficient, we gradually began to think we needed a more spiritual approach. We were very ignorant of such matters, but highly motivated to learn. Accordingly, we started out in a quasi-New Age church that was very much into something called affirmations, i.e., calling things that be not as though they are, with the intent of summoning them into being. Growing dissatisfied with that, we found a movement that seemed more Bible-based and therefore hopefully closer to the source. (For example, the four steps suggested in the image to the left are derived from Mark 5:25-34.) Because of this endeavor, Joseph spent a fair amount of time when he was five and six years old in huge religious conventions and healing services. And his mom and I subsequently spent time coming to terms with the fact that we were either abject failures at this or else were still getting bad instruction. Still, hope is a wonderful thing, and we found some here.

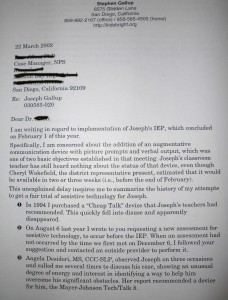

School paperwork

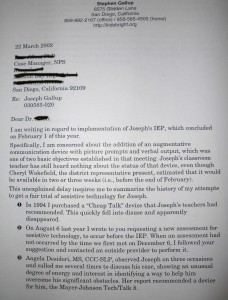

Before becoming a parent, Judy worked in special education. Perhaps for that reason, she knew, very early on, that she did not want educators involved in the decisions to be made regarding our little guy. A couple ladies from the school system came to the house to assess his condition and recommend some sort of special-ed preschool placement. She was not interested. She felt sure they offered nothing that would improve Joseph’s abilities. And so we carried on without any such help until he was seven years old. The time came, however, when he did have to enter the system. That’s when I began learning about what we’d been missing. Over the next several years I accumulated boxes full of IEP reports and correspondence such as the letter shown to the left. (Click the image if you want read the first page, but I’m pointing out that once again the school is not following through with the actions they had agreed in writing to do. In this case, the issue was providing a device that might help Joseph communicate. It’s the identical problem dramatized in Robert Rummel-Hudson’s fine memoir, Schuyler’s Monster.) I hate to look in those boxes. Educators who read this will surely be indignant, but all this documentation bespeaks a staggering waste of public resources and human life.

Before becoming a parent, Judy worked in special education. Perhaps for that reason, she knew, very early on, that she did not want educators involved in the decisions to be made regarding our little guy. A couple ladies from the school system came to the house to assess his condition and recommend some sort of special-ed preschool placement. She was not interested. She felt sure they offered nothing that would improve Joseph’s abilities. And so we carried on without any such help until he was seven years old. The time came, however, when he did have to enter the system. That’s when I began learning about what we’d been missing. Over the next several years I accumulated boxes full of IEP reports and correspondence such as the letter shown to the left. (Click the image if you want read the first page, but I’m pointing out that once again the school is not following through with the actions they had agreed in writing to do. In this case, the issue was providing a device that might help Joseph communicate. It’s the identical problem dramatized in Robert Rummel-Hudson’s fine memoir, Schuyler’s Monster.) I hate to look in those boxes. Educators who read this will surely be indignant, but all this documentation bespeaks a staggering waste of public resources and human life.

Bumble ball

No recap of objects in Joseph’s early years would be complete without at least a nod to those he personally appreciated. He had no shortage of toys, including myriad stuffed animals that well-wishers gave him (alas, he never connected with such things) and so-called educational toys of one sort or another (again, little interest). Thinking back over those days, I believe the one thing he most enjoyed may have been this ball that vibrated and randomly bounced all over the place. Turning it on guaranteed a radiant smile from our little guy, which meant a lot to us adults. (This image comes from Amazon, where apparently it’s now more successful as a toy for pets. Parent reviewers complain about the quality. Maybe this isn’t exactly the same product, but something very similar was a big hit in our house.) All choices Judy and I made were motivated by the desire to maximize his options in life, and yet in the end it all boils down to being happy. Helping a child to be happy is good.

No recap of objects in Joseph’s early years would be complete without at least a nod to those he personally appreciated. He had no shortage of toys, including myriad stuffed animals that well-wishers gave him (alas, he never connected with such things) and so-called educational toys of one sort or another (again, little interest). Thinking back over those days, I believe the one thing he most enjoyed may have been this ball that vibrated and randomly bounced all over the place. Turning it on guaranteed a radiant smile from our little guy, which meant a lot to us adults. (This image comes from Amazon, where apparently it’s now more successful as a toy for pets. Parent reviewers complain about the quality. Maybe this isn’t exactly the same product, but something very similar was a big hit in our house.) All choices Judy and I made were motivated by the desire to maximize his options in life, and yet in the end it all boils down to being happy. Helping a child to be happy is good.