What if This Is Just an Alternative Reality?

One theme very much in favor among authors of speculative fiction/sci-fi is the idea that the reality we experience is one of a perhaps-infinite number of alternative timelines in a multiverse. As someone who has trouble being 100% delighted with current circumstances, I rather like the idea that other instances of myself might somewhere be faring better than I am here, and might even inhabit a better world. There’s a ghost of a sort of comfort in imagining a plane of existence in which certain lamentable mistakes or catastrophes never occurred. But maybe the basic concept isn’t all that new (more on that in a minute).

Authors handle this idea in various ways. For example, one might use it as a workaround for that famous paradox in time travel stories, in which a character goes back in history and makes changes that could result is his never having been born. That scenario could work after all if alterations of events spawned new timelines! The part we’d prefer not to think about is that in a multitude of parallel realities, each one becomes cheapened, perhaps even to throwaway status. If we’re enjoying life in one instance, we’re probably having a rotten experience in another. Nevertheless, the ones we don’t want to think about would be equally real, for somebody.

Backing up a moment, this iteration of the idea comes from the controversial Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum physics, which has been around since the late 1950s. According to that theory, this rational world in which we act and then live with the consequences of those actions is only a tiny slice of reality.

On the atomic level (according to Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger), one can never be certain about a particle’s momentum and position, or about the state of an object when it’s not being observed. Another way of expressing that is to say (1) all measures of the particle/object are equally possible, and (2) even obtaining one actual measurement/observation does not rule out an unknown number of alternative versions, which still remain valid.

By extension, on the macro level—the one in which we live and act—everything that’s possible is actual, somewhere. Every event that could have possibly happened in our past actually did happen in the past of some timelines, and likewise every possible alternative future is also equally real.

Now, my background in physics is weak, but the analogy does sort of make sense to me, in the same way that a model of the atom—a nucleus orbited by electrons—is comparable to a model of the solar system, i.e., that which seems to happen on a very small scale also happens on a very large scale.

Granted, the theory can’t be tested, because outside of fiction there has been no communication among timelines.

Most scientists object to MWI for a variety of reasons, and all of them would scoff at my puny explanation of it. Nonscientists are probably saying all this is too far out there to be interesting. But if you’ve gotten this far, please bear with me a moment more. I’m not presuming to write about science. I’m also not trying to claim that parallel worlds exist, only to describe a way of thinking about our experience of this world. The idea has been around a while.

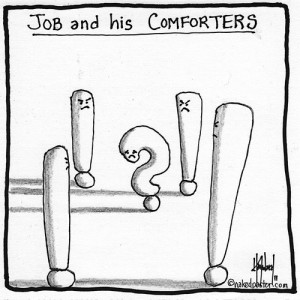

Centuries ago, Western philosophers explained suffering by saying that if something is imperfect, there must necessarily be another instance of the same thing that is perfect (Boethius, Consolations of Philosophy; also Plato’s theory of reality vs ideal concept). Our civilization also has the concept of the Divine Being, which created everything and all of us. This Being is not well understood, but according to Scripture is all-knowing and all-good. Therefore, when tragedy occurs, we’re told that there has to be a reason for it. We cannot perceive or understand that reason, but faith and humility are supposed to sustain us. All will be made clear in the Hereafter. Sometimes, however, the tragedy is so acute that we cannot imagine any possible justification.

I think MWI is a secular answer to the persistent human desire to believe that somewhere—even if it’s over the rainbow—a better, more reasonable world exists. It has an allure, even if we cannot experience it ourselves. That is what prompts people to write and read these books.

Just as points of reference, here are links to commentaries I’ve written on a few alternative-timeline fictions that have come my way over the last few years:

- Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus, by Orson Scott Card

- The Midnight Library, by Matt Haig

- 1632, by Eric Flint

- Dark Matter, by Blake Crouch

- Time and Again, by Jack Finney

- Time and Time Again, by Ben Elton

- Replay, by Ken Grimwood

- Elsewhere, by Dean Koontz

- All Our Wrong Todays, by Elan Mastai

Fanciful or not, the basic idea in these stories has appeal—one similar in kind to the appeal of trying on a new shirt, or imagining living in a different house (knowing as we do the imperfections of the house we now have). Or getting a new president, who promises to restore normalcy. Or even writing off everything as a loss and hoping for better in another lifetime.

On the other hand, that appeal ignores the critical fact that the events of any timeline result from choices made by people. And people, even the smart ones, have a well-established history of screwing everything up.

The vast majority of those now in positions of influence or power don’t give any indication of being smart at all. They’re so obviously incapable of contributing anything of value, one almost wonders how they keep their jobs. Almost. They must be doing what their enablers want. But what are the chances of finding a timeline where they aren’t in charge?

I initially felt drawn to this sub-genre because, in looking back over my life, I see various turning-points where even a trivial decision might have (to channel Robert Frost) made all the difference. But alas there are no do-overs outside of fiction. Also, if allowed a do-over, I’d still end up with regrets.

The impulse to arrive somehow in perfected circumstances seems to be part of human nature, and I guess it’s there for a reason. Still, this side of divine intervention there’s no getting around living with what we’ve done, and what others have done, and the luck of the draw.

Maybe it’s time for different reading matter.

William Ketchum is a rocket scientist who has been retired since the early 90s. During his career he was involved in developing the Atlas rocket, first conceived as a weapon for potential use against the Soviets and later repurposed for America’s first manned space launches. He talks briefly about some of the engineering challenges he dealt with, and includes short profiles of people he’s known (including Buzz Aldrin). He talks about growing up in California during WWII, about the effect of the war on his father, and how living in that environment led to his career choice. After retiring, he did a lot of traveling, e.g., to Pacific islands where his father had been stationed. He also delves into family history and describes the discovery of ancestors who fought on both sides of the Civil War. There’s a section of “weird” stuff he’s witnessed over the years, and miscellaneous speculations.

William Ketchum is a rocket scientist who has been retired since the early 90s. During his career he was involved in developing the Atlas rocket, first conceived as a weapon for potential use against the Soviets and later repurposed for America’s first manned space launches. He talks briefly about some of the engineering challenges he dealt with, and includes short profiles of people he’s known (including Buzz Aldrin). He talks about growing up in California during WWII, about the effect of the war on his father, and how living in that environment led to his career choice. After retiring, he did a lot of traveling, e.g., to Pacific islands where his father had been stationed. He also delves into family history and describes the discovery of ancestors who fought on both sides of the Civil War. There’s a section of “weird” stuff he’s witnessed over the years, and miscellaneous speculations.

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived.

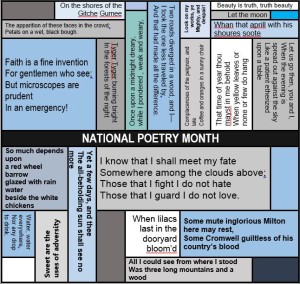

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived. Poems because it’s National Poetry Month.

Poems because it’s National Poetry Month.