De-hunkering

In about 1967, as a geeky high school student, I wore a homemade pin to school one day that proclaimed May 24 as Bob Dylan Day. (That’s his birthday.) One of my classmates, more savvy than most, warned me the idea would not catch on, and of course he was right. Everyone else just wondered who the heck was Bob “DIE-lan.”

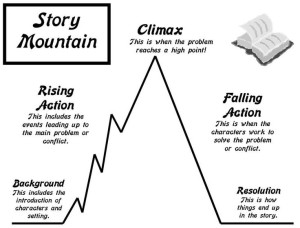

All these years later, Dylan’s still around, and in fact has even scored a Nobel Prize. I’m no longer an avid fan, but his early songs remain imprinted in my brain. Thus, one night earlier this month, when an online discussion via Disqus happened to segue from talk of the coronavirus to Dylan lyrics, I experienced a flash of quasi-creativity and repurposed one of his oldies as follows:

Well Xi said to everyone “It didn’t start here”

Everyone said “Xi, the facts are pretty clear”

Xi yelled “Silence!”

Everyone yelled “Pooh!”

Xi said “Don’t matter what you might think is true

When I can make every one of you losers disappear!”

Everyone said “All right, so what is it you expect to hear?”

Xi said “Just go repeat what I say on that Western blogosphere.”

Well at home the Donald was feeling irate

His numerous rivals were claiming checkmate

He told his aide, “Their behavior’s just insane”

Aide said “Sir, try not to pull their chain”

Donald said “Pay attention: here comes my best bronx cheer!”

Aide said “Show them instead how to get through this year

Because for most folks the main problem is fear.”

“Well, bean counters,” said the company chief

“If we’re not doing business we need some relief

Payroll’s killing us. We’re gonna come to grief.

I need a way out! I need a fig leaf!”

And the bean counters said “It’s just a temporary change of gear

Folks need to hunker down till there’s an all-clear

At which point they’ll resume their careers.”

Now the aged granny in quarantine

Told her aging son she didn’t feel so keen

“In fact,” she said, “I’m coughing till I’m green”

He said “It’s the nastiest epidemic I’ve seen.

There needs to be some regression toward the mean.”

But the mean, he found, was slow to reappear

He had to stay at home, couldn’t even volunteer

Depleting groceries as life grew more austere.

Now the valiant doctors kept at it every day

Treating the victims from New York to Taipei.

When asked about hydroxychloroquine they’d reluctantly say

“With it there’s a chance of making headway

Or with some other meds, if endorsed by our peers.”

But somehow every hopeful claim met with jeers

From a hundred points of view that would not cohere.

Well the passing weeks brought more and more pain

From vanishing jobs as the threat slowly waned

While petty would-be tyrants added to the drain

Saying “Do as you’re told. It’s we who’ve got the brains.”

Until folks up and said, “This plan is a clunker.

We’ll take our chances; we’ve got to dehunker.

Those who object can remain in their bunker.”

Someone on that thread remarked, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”—indicating he recognized my source.

Sure, this is derivative. It’s just a way of making a point.

And regarding that point, I added the final verse more recently, to acknowledge the direction this ongoing crisis has taken.

And now I’m adding the whole thing to this long-neglected blog because I cannot avoid seeing it in a personal context—it being this notion that remote authority figures get to dictate the choices each of us needs to be making for ourselves.

That issue came up years ago on publication of my memoir, What About the Boy?, which describes the very nonstandard approach my wife Judy and I took in trying to find help for our disabled little boy.

One reviewer, in the UK, wrote at the time “I was very surprised that … nothing happened when they showed the doctors” the home therapy being implemented. What the reviewer clearly expected to happen was intervention by some authority figure to prevent us from attempting to help our son by unapproved means.

But you see Judy and I had resorted to those unapproved means because mainstream doctors had already made crystal-clear that they would not be helping him. That was the thrust of the first several chapters in the book: Repeatedly, we begged for help and guidance, only to be told nothing could be done.

Despite the fact that they hadn’t even diagnosed his problem.

Our reaction might have been different if the doctors—the experts—had inspired confidence that they knew what they were doing, or that they cared. But our perception was that (1) they knew nothing about his condition, (2) they had no curiosity, and (3) they found all our questions tiresome. So, loving our son and feeling responsible for his well-being, we took it upon ourselves to learn about alternative methods.

I am also reminded of the plight of another family with a disabled kid (in the UK, it turns out) who have no say in the matter of where their son lives or even whether he can come home for visits. They have been fighting that battle for years—and losing it, because their rights, and their son’s expressed wishes, count for nothing. The mum has bitterly concluded their government agencies know a “cash cow” when they’ve got one.

I don’t want to live in a country that doesn’t recognize individual liberty. For sure, each of us can and will make mistakes, and yes of course we should turn to resources for more information. But since we are the ones who live with the consequences of what we do, we need to be able to choose freely.

My wife and I had an imperfect response to our son’s developmental problem. We paid a significant cost, which we didn’t fully understand at the time. But we helped him! I regret that we couldn’t help him more than we did, but I do not regret having given the cause our best try based on what we knew at the time.

Back to this hated virus: Last week an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal observed that an “overclass” consisting of experts and political figures is “calling the shots for the average people,” despite the fact that “they have less skin in the game.” In many parts of the country these so-called elites are making decisions such as who is permitted to reopen a business or go back to work. There are no consequences to them if they err (and err they do), but disastrous consequences to the citizens affected.

Yes, one may argue, but there is “the science,” the danger of new infections.

Yes indeed, comes the rebuttal, but that does not take all the issues into account. One: There is the economic necessity of avoiding an all-out Depression, and the individual necessities of preserving important things people have worked for. Two: It’s now apparent that the lethality of this disease was drastically overestimated. It’s very bad news for the elderly and for those with underlying conditions like diabetes and obesity. Anything we do must take that fact into account. And evidently people do recognize this. (I do. Given that I was in high school in 1967, you know there’s some risk to me.) It’s in our common interest to resolve this. But you can’t expect everybody to stay home until such time as a vaccine has been created. Nobody who willingly stood down for a while, to “flatten the curve,” agreed to that.

Much of this drama, I am convinced, has less to do with public health than with an opportunity to establish greater power over you and me. Because the people in charge think they know what we need more than we do. I did not give up the right to make choices on behalf of my son, and I believe my fellow citizens see this the same way. We simply must. And, after all, this is also a precedent.