Henry Ford, the entrepreneur who showed a younger world how to get things done in a big way, has been credited with this gem of wisdom: “If you think you can do a thing or think you can’t do a thing, you’re right.”

I was reminded of that today when writing a short remembrance of another pioneer, Ray Bradbury. The story in WATB, and my ongoing ruminations about what it means, amount to an exploration of the limits of what we can do.

Here are more nuggets from Mr. Ford, and my current thoughts on their application:

“Time and money spent in helping men to do more for themselves is far better than mere giving.”

To me, this is a variation on what Glenn Doman said back in 1986: that the right objective for Joseph was that he be “an answer to the world’s problems, rather than another of its problems.” I understand that some disability and diversity advocates see things a little differently. My short answer to them is that it boils down to having options. Someone who has the choice of affecting the world around him is better off than someone who depends on that world for everything that happens. Assuming he makes wise choices, other people are better off as well.

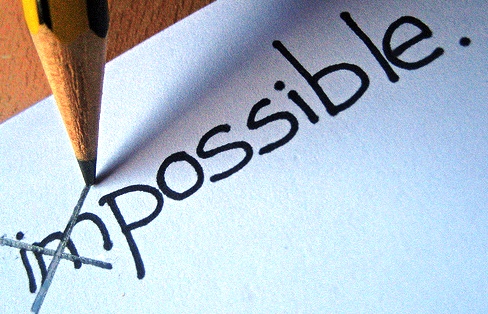

“I cannot discover that anyone knows enough to say definitely what is and what is not possible.”

When Joseph was one year old, his doctors transitioned from telling us to be patient and hope for the best into telling us to get counseling, so that we could cope with the fact that nothing could be done for him. At least, they proposed doing nothing for him, and they warned us to stay away from any alternative providers who might have a different take on the situation.

Those doctors lost all credibility in our eyes when alternative providers did in fact help him.

Did the alternatives have all the answers we needed? No. Were they as smart as they seemed to think they were? Alas, they were not. This was doubly disturbing, since they claimed as adamantly as had the original doctors that no answers existed outside their own specific realm. Again, we were advised not to look elsewhere.

If we had been less motivated and more convinced that we were getting the complete picture, we might have reacted differently. But when you have a problem that you feel absolutely must be solved, and the known resources for solving it no longer inspire confidence, something happens in your head. At least, something happened in our family. We set out on a quest for answers with no guidance beyond what felt right.

Were we smart enough to do that? Probably not. But we didn’t want to give up without establishing for ourselves the potential of every plausible course of action. I cannot regret our choices.

“There is joy in work. There is no happiness except in the realization that we have accomplished something.”

When I’m asked to talk about WATB, a point I always try to make is that, despite having a child with profound developmental problems, and despite being busier than we’d ever been in our lives, Judy and I spent a great deal of the time feeling extremely happy. Optimism reigned in our household. Volunteers who came to see us felt energized, and no doubt that was the reason many of them kept coming. We believed fervently in the rightness of what we were doing. We saw evidence in our son that reinforced that belief. Those days were an extraordinarily upbeat time in our family’s life, and I look back on them with wonder.

“Thinking is the hardest work there is, which is probably the reason why so few engage in it.”

It isn’t easy to think clearly when in the thick of battle. Also, one’s thinking is only as good as one’s knowledge, and throughout the story I tell knowledge was never in great supply. We started off with basic instincts and notions of right and wrong, and that arsenal was what informed a lot of the decisions made along the way.

But the writer writes to teach himself, and a lot of my deeper thinking on the subject of our campaign took place as I was putting my book together. So far, this thinking hasn’t particularly benefitted Joseph. It has, however, enabled me to bring new understanding to his extraordinary childhood and current status. Further revelations continue to take shape as I blog about the story. This is not a linear process. Time passes with no new insights. But then something clicks and my understanding acquires new depth.

This latter phase was optional. The story could have ended without my ever having digested or told it. I have benefitted personally from going back over it. My hope is that readers following the thinking that it dramatizes will see things anew in their own lives as well.

“Failure is only the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.”

From a practical standpoint, the first motorized quadicycle Henry Ford built wasn’t much of a vehicle. The first car company he put together didn’t exactly work out for him, either. The same can be said for the first several attempts Judy and I made to help Joseph. We took our son to doctors and therapists who, quite frankly, had other priorities that prevented them from giving his case the kind of attention it needed. We saw other providers whose frame of reference was too narrow, if not altogether wrong.

Every time a resource disappointed us, we looked for another. We looked to ourselves, as well, because early on it became obvious that nothing was going to happen that did not involve major effort on our part.

Several milestones and several plateaus later, to use automotive metaphors, we ran out of gas. We reached the end of the road. If further progress for Joseph is yet possible, the route it will take has not yet been surveyed.

However, my pledge to my son, alluded to in the book’s subtitle, is that I remain poised to resume the effort when a new course of action looks promising. I will do so armed with everything learned along the way. The result might yet be an answer to the world’s problems.

On Monday, Adam Scull of Write On America interviewed me as part of his interesting series of conversations with writers across the country. I’d originally introduced myself to him as a technical writer, since (can’t deny it) tech writing accounts for the bulk of what I do with words. So I expected questions about that side of the sport. But then somehow I blew past his only reference to that, and we focused instead on memoir writing.

On Monday, Adam Scull of Write On America interviewed me as part of his interesting series of conversations with writers across the country. I’d originally introduced myself to him as a technical writer, since (can’t deny it) tech writing accounts for the bulk of what I do with words. So I expected questions about that side of the sport. But then somehow I blew past his only reference to that, and we focused instead on memoir writing.