Let’s Not Let It Slip Away

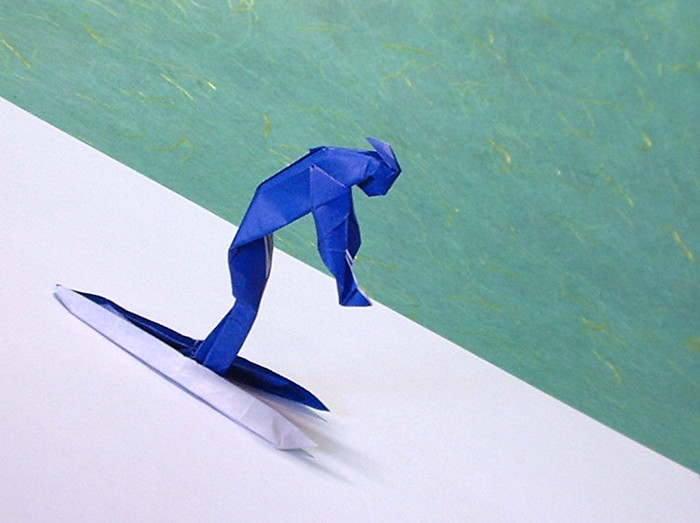

Try this experiment some time. Let’s say the conversation going on around you concerns sports—college, pro, doesn’t matter. At a pause, casually mention, with a straight face, “Did you guys know they’re adding origami as one of the Olympic sports?”

Observe the reactions of those around you. It’s a ridiculous idea, of course. Folding paper is a pastime, a hobby, perhaps an art form, but not a sport. And yet—is this idea all that strange, in the context of what’s going on in the world these days?

I predict (if you can avoid smiling) your friends will believe you. They’ll mutter, “No,” but in a bewildered, disgusted tone. They’re already primed to accept further evidence that the world has utterly lost its moorings and is increasingly becoming unrecognizable.

Then you can relieve them with the punchline: “But it’s only going to be pay-per-view.”

Plausibility is what gives the joke its edge. These days, bizarre changes, affecting everything we hold near and dear, are coming at us as if from a firehose. They keep us off-balance, and I think that’s by design. We can’t push back, not at everything! It might be okay if they were the kind of changes that make daily life more convenient, or if they represented advances in medicine or technology or knowledge of the cosmos. There’s been some of that, thankfully, but most of what we hear about are attacks on things that a lot of us thought were just fine as-is.

I guess news of the attacks makes for good headlines, good ratings. The media companies thrive by shocking their consumers. (Also, a population focused on one big story may miss some other development that the opinion-shapers want to downplay. I don’t need a tinfoil hat to say that much, do I?) And sure, media being what they are, the story is often exaggerated, blown all out of proportion, even (to fall back on an overused word) fake. Also, it generally is not presented as a bad thing. On the contrary, any bad guys as such a story unfolds tend to be the ones who object.

Even recognizing that change has always been an inescapable part of life, there’s no denying that we are suddenly being asked—no, told—to accept without demur radical departures from the most basic, fundamental concepts that have been underpinning civilization throughout history. In academia, industry, and government, people have been installed in prominent, well-paid positions from which they are telling us how it’s going to be henceforth.

Do I need to be specific about the long-held understandings that are now supposedly wrong? I don’t think a bullet list is necessary. You can supply examples, any one of which could take this post down its own zany rabbit-hole. Also, a list would rapidly become yesterday’s news, because it should be obvious to all that the train of upheavals is not stopping. Over the next year, the next five years, and beyond I guess, there will be more. What would it take to satisfy whatever, or whoever, is driving this? What would have to be achieved before the revolution stopped? I think it has already been established that utopia on almost any scale is beyond human grasp. Or is that lesson also no longer true?

Fair disclosure: I’m an old fart. Down through history old farts have been complaining that the world is going to pot, because their remembered or imagined good old days have passed away. I acknowledge that, but the phenomenon we are now seeing is something altogether different. No previous era has experienced such drastic change, driven by a self-anointed set of influencers, on such a broad scale.

Again, I’m striving not to cite examples, because any careless imposition of change, in itself, prompts thoughts of Chesterton’s fence. The fence is a metaphor for anything inherited from previous generations. If we assume those who came before us were ignorant, unenlightened fools, far inferior to ourselves, then we may tear it down without first asking whether it was put there for a good purpose.

Understanding whatever purpose it had, and maybe has, and discussing that purpose in good faith, calls for some critical thinking on everyone’s part. Maybe the time for pulling down that old fence has truly arrived, but we won’t reach agreement if one side relies on ad hominem attacks against the other.

Often, that’s the way these things unfold.

The discord is what led me to type up these thoughts. My sense of alarm has been building for years now, but I began to sense what the best-case solution upon hearing a pastor mention the famous aphorism, attributed to a contemporary of Martin Luther’s, “In essentials unity; in non-essentials liberty; in all things charity.” The pastor was talking about variations in dogma and practice among believers (e.g., whether it’s okay if some Christians celebrate Halloween). I immediately adapted it to the more secular issues that worry me.

What are the essentials in our society about which there has to be unity? In any dispute, that is the question that cannot be pushed aside. No matter how much importance or urgency somebody claims for the cause du jour, is there anything else that we agree must not be sacrificed in dealing with it? Assuming essentials are not in danger, then we are free to find a path forward that respects the rights and interests of those who want a given change and those who don’t. Because of the common ground we share, we should be able to disagree on lots of subjects without saying the other side is subhuman. That’s the charity available in following the above rule.

I still think there are enough of us capable of responding constructively if issues were raised and addressed in terms of our common ground. I think, or hope, most of us still value that common ground.

The alternative would not be a best-case solution. I would be one in which everybody loses, some now and the rest very soon.

Yesterday, following a typical morning round of errands, I found myself back at home relaxing in my favorite chair when my adult son Joseph approached with a request.

Yesterday, following a typical morning round of errands, I found myself back at home relaxing in my favorite chair when my adult son Joseph approached with a request.