Peak Reading Experiences of 2017

This blog came into being as a backup to the memoir I wrote about raising my disabled son, who’s now 32 years old. In the years since publication, I’ve posted occasional updates about Joseph as well as odds and ends about striving in general.

I used to think the campaign to improve my Joseph’s prospects would be the ultimate uphill battle of our lives, but recent years have brought major new challenges. For example, in early 2016 he was diagnosed with melanoma. Since then he’s had some very low times, but excellent medical care keeps him going. Simultaneously, I went through a three-year period of unemployment and marginal employment—from which I’ve only recently emerged. As we finish out 2017, Joseph is comfortable and in good spirits and I am finally beginning to breathe easy regarding my prospects for continuing to support the family.

Going forward, I don’t expect to be reading as much as before—because I’m no longer commuting as much—but right now I can choose from a vast array of titles consumed this year to offer the following recommendations of my faves for 2017 (in no particular order). And by faves I do mean the best of the best. I encountered more than the usual number of outstanding books this year. Long-distance commuting did have an upside.

Clicking the titles below will take you to more complete write-ups on Goodreads. And, fwiw, my lists of books for previous years are here: 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011. By the way, printed copies of WATB may not be so easy to find these days (unless you contact me directly), but ebook and audio versions are still available.

If you’ve seen or heard about the movie (which I also recommend), you know Wonder is the story of a 10-year-old boy who until this point in life has been sheltered from the outside world because he has facial deformities. But now his mother has decided the time has come for him to venture outside the protective bubble. The process does not go smoothly.

This story strikes close to home. Joseph has an unnamed condition that, like August’s, is probably genetic. His physical abnormalities are subtle, but in terms of function he’s profoundly disabled. It’s a matter of opinion as to which would be worse, this or August’s horrible deformity coupled with normal intelligence and ability to communicate. Either case means hitting a lottery nobody wants to win.

The author’s intent is to ask how the rest of us will treat people like August. One of the characters says, “The universe was not kind to August.” True, but we can be kind. In doing so, we may even discover a greater affection for ourselves and for one another.

When Breath Becomes Air, by Paul Kalanithi

This book is at the intersection of subjects that have been very important in my life, memoir and medicine, literature and illness, striving and accepting. It has additional gravitas in being the only, somewhat truncated literary effort of a young physician who’d thought he might do some writing in old age but altered his priorities upon the discovery that he was dying.

Seen in its own terms, his story is absorbing, poignant, tragic. I see it in terms of my own experience, as the author and I are almost mirror opposites, but it can speak to anyone, especially in terms of our efforts to maintain control over circumstances—and what to do when that control is gone.

The Pleasure of My Company, by Steve Martin

Somewhat lighter fare here! Daniel Cambridge enjoys the presence of several attractive women in his life: the wannabe shrink who comes by twice a week to evaluate his progress in overcoming neurotic habits, the pharmacist who fills his prescriptions, the neighbor who doesn’t know visiting with him is so enjoyable because he spikes her drinks with small doses of his meds, and the realtor who thinks she’s going to rent him a new apartment.

This story is laugh-out-loud funny. It’s also heartbreaking, because Daniel’s situation is so recognizably human. Ultimately, it’s mind-expanding, life-affirming, beautifully structured, and just plain good.

As one grows older, and looks back at the turning points of life, it’s probably natural to wonder how differently one’s story might have unfolded with a few different decisions. Neil Countryman and John William Barry are alike in many key ways. Both love hiking in remote areas of the Pacific Northwest. Both have an intense desire to do the right thing, regardless of the cost. In a sense they could be viewed as different iterations of the same man, and Guterson’s description of their different fates could be this kind of meditation.

I’ve probably read everything by David Guterson (who’s best known for Snow Falling on Cedars). He never disappoints, but this might be his best to date.

All Our Wrong Todays, by Elan Mastai

Here’s another treatment of the theme of alternative paths. But its main thesis is that every good thing has a fatal flaw—a way in which it can become just as bad as it was good. The big question is how one claims the good while avoiding/minimizing the bad (or whether one has enough information to judge).

Aside from that philosophical speculation, the story works fine on its own terms (it’s sci-fi), and there’s wonderful dialog as well as a great many quotable epigrams. (BTW, my best books for the year are books I was lucky enough to read this year; they aren’t necessarily new. However, AOWT was published in February 2017. Take note of this author. I expect he has more great stuff on the way.)

The Dead Fathers Club, by Matt Haig

Several books crossing my path of late have been modern reinterpretations of classics. This re-imagining of Hamlet, narrated by the juvenile heir of a British pub, is my favorite of that lot. One reason for liking it is that, rather late in the story (and just in time), it departs from strict adherence to the original. When doing so makes sense, authors should treat their characters with some degree of benevolence—especially after making us care about them.

Let the Great World Spin, by Colum McCann

There’s worthy precedent for a large, sprawling novel set on a specific date, in the context of known historical events. I’m thinking of course of Ulysses, which is a very tough act to follow. Kudos to Joyce’s countryman Colum McCann for rising to the challenge.

He does not merely make us care about his characters. I for one realized partway through that I loved them.

The Book Thief, by Marcus Zusak

“Even Death has a heart,” we are told, and I guess we should believe it since it’s Death himself who says so. After all, he cares enough to serve as the narrator of this wonderfully devastating story about people striving against the odds to stay alive. It’s an extraordinary story, with exemplary use of language, and the audio version is just superb.

Willow, the narrator of this novel, describes life in rural China beginning in the waning days of the Qing Dynasty as she grows up alongside Pearl (later to become the real-life author Pearl Buck). Arriving at adulthood with causes for sorrow, both women begin finding consolation through writing. New troubles ensue when Pearl encounters social engineers who are birthing the new communist state. They want to censor ideas not supportive of the Grand Revolution, whereas Pearl argues that readers should be free to decide for themselves what to read. In due course she is exiled and Willow endures the imprisonment and reeducation that are familiar from so many other accounts we’ve had from that country.

The conclusion is very touching, and a reminder that this has less to do with turmoil in China than with affection between two soul mates. If Willow is a fictional creation, I suppose she represents the author’s response to learning, many years after Pearl Buck’s death, who this woman was.

Oracle Bones, by Peter Hessler

This first-person depiction of China joins a long list of similar accounts I’ve read over the years. It feels like a memoir, although a unifying narrative arc is not obvious. There are narrative threads, of course: concerning not just the author but also the friends he made there. I was quite taken by his own challenges (surviving on a freelancer’s uncertain income, offering friendship across a significant cultural divide, avoiding arrest). For context he weaves in background regarding both ancient history and recent trends in Chinese society. I especially appreciated his commentary on the origins of and logic behind Chinese writing (speculative though those origins may be). Despite abrupt transitions, it all hangs together naturally, and I’m very glad to have read it.

(Incidentally, I enjoyed an email exchange with the author after my commentary appeared. He’s still immersing himself in and writing about other cultures and no doubt has more excellent books on the way, all of which I hope to read.)

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, by Angela Duckworth

My list would not be complete without at least one more nonfiction representative, and especially (given my fixations) a title concerning goal achievement. Grit amplifies the concept expressed most succinctly by Edison, about success being mostly perspiration as opposed to inspiration. That is, while it’s great to be talented and clever, etc., tenacity is the most important trait. From there, the author provides specific steps for applying tenacity to actual achievement and persevering through setbacks and adversity.

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

Many years ago, a young mother tried to make sense of the observation that my wife and I had a baby with major developmental problems. Surely, she insisted, Judy must have smoked or used drugs while pregnant—or at least we’d done something to merit that outcome. What was it?

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived.

As I sat here writing this, I began wondering how much life would be different if we lived under some kind of curse—if a vengeful deity were consciously extracting the maximum amount of sorrow, granting only enough encouragement to ensure we continued wandering about in the maze. I don’t believe that, but such thoughts do suggest themselves. At this moment, unbidden, my very affectionate nine-year-old has come along and flopped into my lap for a snuggle. Earlier this year, he too had a brush with mortality (a close encounter between a moving car and his bike). I’ve not forgotten my gratitude that he survived. Poems because it’s National Poetry Month.

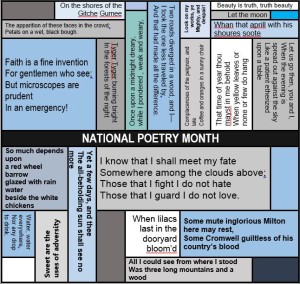

Poems because it’s National Poetry Month.