A review of The Man in the Empty Boat

I first encountered Mark Salzman’s writing when participating in a memoir writers’ critique group that met over a period of a couple years. The group leader suggested Lost in Place as a good example of the genre. I thought it was a wonderful book, and (after finishing my own memoir) went on to read his other works.

Along the way I decided that Salzman is a writer whom I would particularly enjoy meeting and getting to know. Perhaps that’s because, as he mentions in this more recent memoir, his characters, real and fictional alike, are “tormented by the gap between who they actually are and who they had hoped to become.” It’s likely that everybody in the modern age experiences that disconnect to some degree. I certainly do. In this book he shows, more explicitly than before, and with much humor at his own expense, that it’s true of himself. His achievements, while pretty darned impressive from where I sit, do not impress him.

To some extent, that’s due to having set rather lofty goals. He says, regarding his adolescent ambition of attaining true enlightenment: “Wise people adjust their expectations. They stop comparing themselves to Buddha or Batman and trust themselves to achieve their personal best. Not me; I was not going to capitulate … I was not going to be a quitter.”

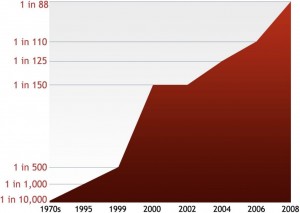

That is precisely the way I felt about the campaign I waged for several years to rescue my little boy from a mysterious developmental disability. Didn’t matter how difficult the task became, or how many discouraging comments I heard. I intended for us to reach our objective!

Popular culture encourages that kind of thinking, through all the familiar stories about the underdog who finally prevails against overwhelming odds. And I’m not prepared to say that’s a bad thing. We should hitch our wagon to a star.

But somehow we also need to find a perspective that allows us to survive reality without coming unglued. Maintaining that perspective requires work every day, and some days a lot of work. The Man in the Empty Boat focuses mainly on 2009, an unusually difficult year for Salzman (and for me, come to think of it). During that year he began suffering debilitating panic attacks (although he didn’t know what was happening and reasonably supposed death could be imminent), he was compelled by the family to accept a very objectionable pet into his life, and worst of all he witnessed his sister’s death, described here in agonizing detail. At the lowest point, he admits:

“At that moment, I asked myself: If there was a button I could press, and I knew that pressing it would make every human being on the planet disappear instantly, painlessly, forever, without a trace, so that the whole bonfire of fear and hope and confusion and pain would be over with, once and for all–would I press it? My own children, I reminded myself, would dissolve along with everyone else. Everything dear to me, and everything dear to everyone else would disappear. So would beauty, courage, love, tenderness, curiosity, ambition, art, science, technology, history, knowledge, consciousness–all of it would be erased. Would I press that button?

God yes, I thought. I would press it in a heartbeat. And I felt truly sorry that no such button existed.”

He returns to that thought in the concluding chapters, first using it as a framework for a new understanding of life (actually, we are all in the process of disappearing–albeit very slowly) and finally, after considerable thought, promising that the button has lost its appeal.

One admirable aspect of Salzman’s life that he scarcely mentions here is his music. According to his official biography, ability to play the cello facilitated his acceptance to Yale at age 16, and he has played with Yo-Yo Ma at Lincoln Center. (By way of contrast, a previous blog post covers what I’ve done with music.) I’m also envious of his fluency in Mandarin (my progress in that language plateaued long ago) and, to be blunt, of the fact that money doesn’t appear to be too much of a consideration in the life portrayed here. I suppose, in wishing to know him, I really want to understand the path to enjoying the blessings he has, even if more would have been nice.

But sometimes, at least, answers come unexpectedly, from unlikely sources. One clue presents itself at the end of The Man in the Empty Boat, conveyed with Salzman’s trademark humor and reliably vivid writing. I now think he has spelled it all out as clearly as is possible.